KIRIN . PEQUEÑA RETROSPECTIVA

August 16 to September 27, 2024

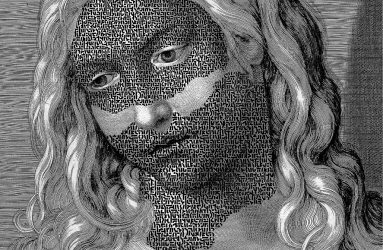

The Translation of the Hieroglyph

By Pablo Gianera

The gaze that an artist directs at their past work is never nostalgic (in the sense of what could have been done differently, or worse: what could have been done before and can no longer be done). No. This review is aimed at detecting unnoticed causalities. It often happens that the artist unknowingly invents the causality of their oeuvre, and the detection adopts, even for them, the surprise of discovery. The discovery, in its pure novelty, excludes nostalgia. The necessity of a preceding work is revealed in the one that followed it; even more: the subsequent work creates the necessary condition for the previous one. By making this gaze public – the retrospective – Kirin involves the observer in determining which quarries of nature were exploited, or which work, their own or someone else’s, was demolished to continue making theirs. The retrospective integrates the work into history (there are at least two histories: the artist’s own and the history of their art), but when a work is as strong as Kirin’s, it does not need the crutches of interpretative continuities, and each work stands alone as if no other work had existed before or after, as if the artist themselves had made no work before or after.

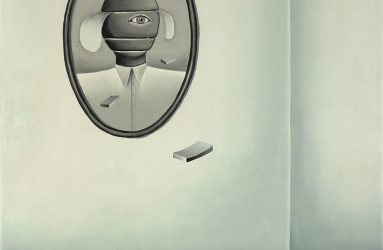

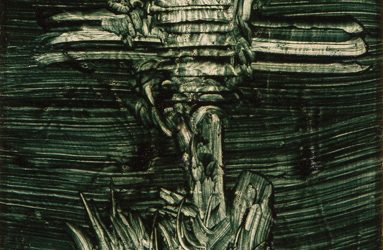

The Lantern of Dreams (p. 1) is the incipit. The geology student Kirin encounters the dreamer Max Ernst. That painting is evidence of the encounter, although, like any initial encounter, it falls into the misunderstandings of infatuation between one who wishes to disengage from materiality, from the earth, and one who realizes that the only way to transcend materiality – dreaming – is through matter (despite everything, geology and dreaming – and dreams – can get along quite well, as Novalis proved). From Ernst’s landscapes, in that very early Kirin, remains the obstinacy of objects; objects that we do not know what they are, but that we know are objects. This tenacity continues, though now with a Magrittian inflection, in Under the Leaves of Your Eyes and Tears (p. 10).

Surrealism was initially something literary for Kirin, in the strict sense of the word: an avant-garde that existed only in the written word. The cause of this mutilation was the Anthology of Surrealist Poetry prepared by Aldo Pellegrini in 1961: the only images in the book were the portraits of the poets, but there was no painting there. But there Kirin would have read the poem “Max Ernst” by Paul Eluard, with the verses “In a corner the liberated sky / Delivers white spheres to the thorns of the storm.”

The meaning of these closed verses, which come from an image we are unaware of, cannot be opened with words: it requires another image to restore its origin. Kirin found, with the certainty of a sleepwalker, that two-way path between image and word, the path of its secret causality.

The allegorical correlate of this unseen causality is the encyclopedia. Just as the retrospective observation of a work, the “encyclopedic” reading is never total but fragmentary. Looking at the images of an encyclopedia is quite similar to composing a collage; two dissimilar images on a plane that differs from both: the imagination. The imagination? That is, literally, yet to be seen.

One could say of Kirin what was precisely said of Ernst, that “he always liked to cultivate the visions of half-sleep”; but half-sleep, demi-sommeil, is not rêverie, daydream. Kirin does not imagine or plunder daydreams. Nor is he unaware that half-sleep is tortuous; the one who “half-sleeps” would like the daydream but does not reach it because objects deny it to them (objects are not just mere matter; they are also disappointment, betrayal, melancholy, joy). Kirin knows that those who see do not need to imagine; imagination is here the consolation of those who see nothing. It is with the intercession of those seen objects that half-sleep transfigures – an exchange of objects – into a hard-earned work of art.

Kirin’s poetics is therefore one of attention rather than imagination. Attention understood as Cristina Campo understood it; attention as waiting, fervent acceptance, courageous acceptance of the real. Campo adds: “Like the genie of the bottle, the attention of the image releases the idea and from the idea gathers the image […] Thus justice is fulfilled, destiny: that dramatic dissolution and recomposition of a form. The expression, the poetry thus born, cannot be, evidently, anything but hieroglyphic, like a new nature.”

There are traces in Campo’s assertion of a formulation by Novalis: “Die erste Kunst ist Hieroglyphistik,” “the first art is hieroglyphic.” The conclusive brevity of the sentence might conceal or disguise a twist. “First” does not imply a chronological allusion here (if it did, the verb should be in the past, as if we said, “the first art was hieroglyphic, but now we can understand it”). What is meant is that the only art that counts is hieroglyphic.

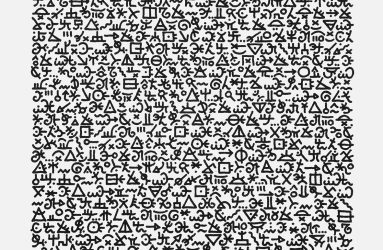

The hieroglyph is, for those who do not know how to read it (and what is inherent to the hieroglyph is that it always retains its mystery, that no one can ever know how to read it), an image, but not just any image; it is an image of writing. The hieroglyph is the writing cipher of the infinitely partial, opaque understanding of the world’s objects. Only those who know a lot, like Kirin, possess the means to represent that lost state in which what could be understood was contemplated.

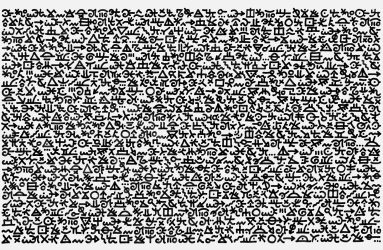

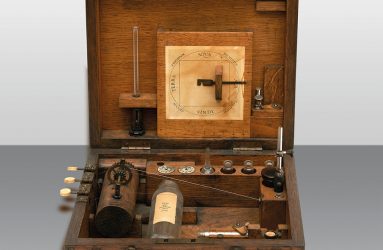

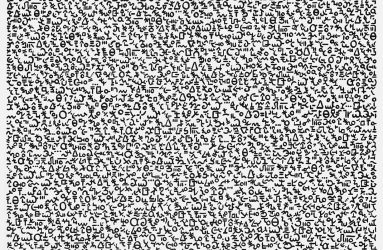

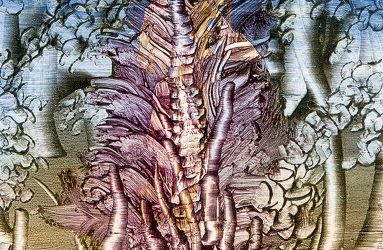

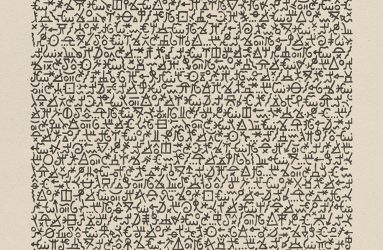

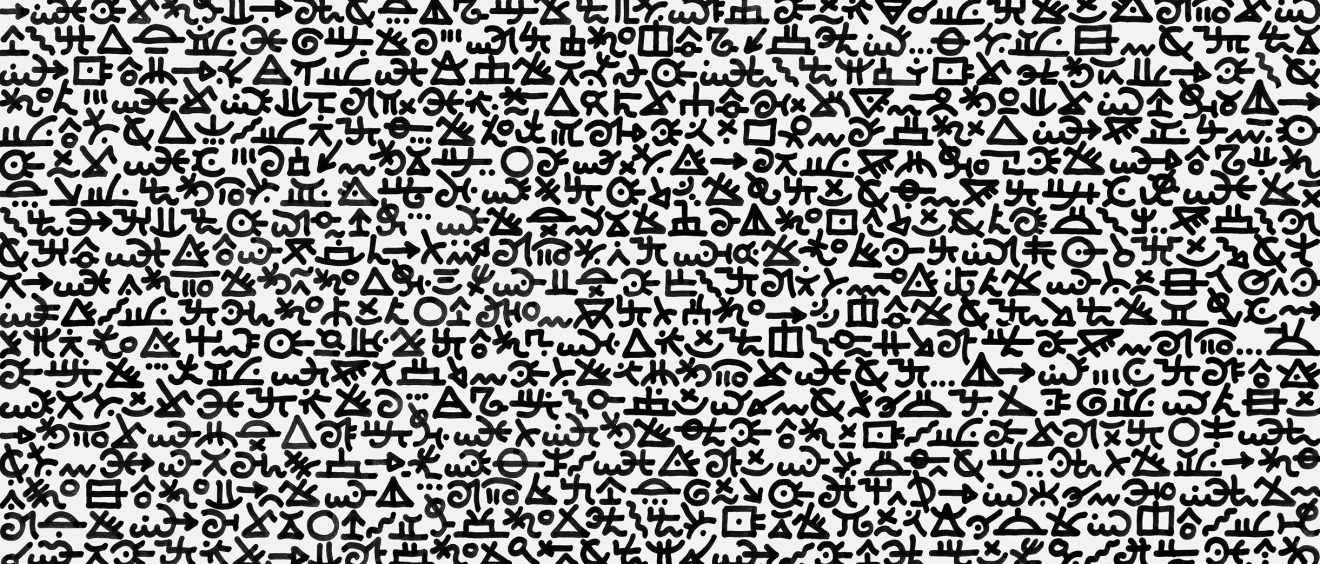

This hieroglyphic writing, thus understood, is the center of gravity of Kirin’s poetics. It began to prepare, unbeknownst to the artist, long before the Scriptures series (pp. 65-77), later scattered, and also reaches the “music” of the luthier Kirin, and his instruments that recall forgotten sounds, or sounds that no one had discovered, the line turned into a staff, into a writing untranslatable to another language and understandable only in its own terms. Music is the darkest of the arts (“dark,” meaning hidden, opaque), but it is because it encloses the secret, the revelation (the equation of secret and revelation resolves in mystery). Kirin’s work confirms the fulfillment that music, time, becomes space, and painting, space, becomes time. Sight and hearing become interchangeable: time is seen, space is heard. What is revealed is not of this world, but even if it were, what matters is not that. What matters is that what is revealed is in plain sight, and what is in plain sight demands attention.

The observer cannot escape the spell that what is seen remains a writing; a writing that says something, something we cannot translate and much less read. We cannot do it because it does not refer to anything beyond itself. Even monochromaticism suggests writing: a robust writing, rune-like, with that hieroglyphic enigma of all art. Writing can be the subject of painting, if only for the simple fact – not a novelty – that painting itself is a variety of writing. It is the lovers’ relationship between pen and brush. All the perplexities of art are the perplexities of language. Kirin convinces us again that all art evokes a lost language (which is not the same as a dead language) and guides us to another yet uncoined.

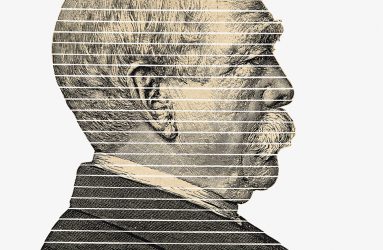

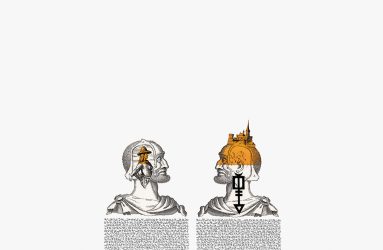

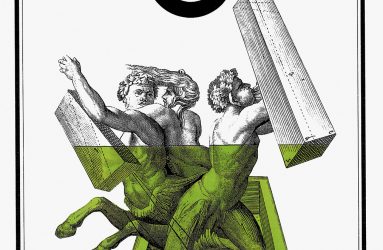

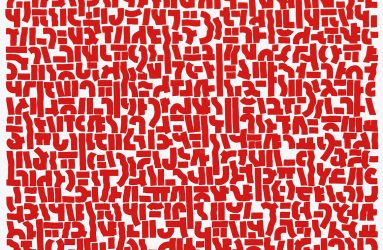

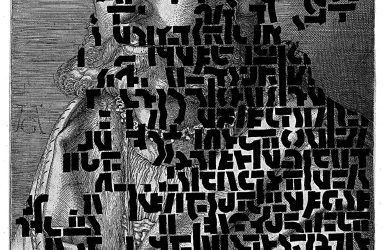

In the Diderotica series (pp. 111 ff.), the starting point is the encyclopedia of encyclopedias, the Enlightenment L’Encyclopédie, that “rational dictionary of sciences, arts, and crafts, by a society of men of letters, first published in 1751 by Denis Diderot and Jean D’Alembert, which aimed, as stated in its “Preliminary Discourse,” to “expose the order and correlation of all human knowledge.” Kirin, for his part, understands enlightenment in a literal sense, which nevertheless brings with it the philosophical sense. He extracts, often from the Internet, those ink drawings, expands them until, by virtue of pixelation, they conquer abstraction. In other cases, like in the oil paintings on paper, the illustration is buried, intervened to extinction by the color red, the only one in the series.

Perhaps Kirin also intends to hint, with the color of blood, at the terror that resides at the core of Enlightenment reason: the encyclopedic Kirin is kept in check by the romantic Kirin. Both are confounded – become one – in Novalis, whose Fragmente was precisely his Encyclopedia. Also in both – in Novalis and Kirin – the systematic rigor of form and the rule of incalculable brightness coexist without conflict.

The old dilemma between reason and dream thus finds a new turn in Kirin’s works. The figuration comes to his art from the outside, from the illustrations of the encyclopedia, which continue to illustrate, in absence, even though the definition of what is illustrated is missing. The definition of what is illustrated is missing because it can never be completed: brightness is the concealment of what demands to be defined; and the brightness itself, indefinable, is the only definition we have. That oscillation is no different from the hieroglyph. We are faced with the same and unique enigma: the meaning of the image and the impossibility of translating the image into language; better said, the always postponed possibility of enclosing the image in a meaning.

Kirin introduces an exception to this rule: a naked image from L’Encyclopédie, a hand holding a quill and the entry “Art d’Écrire.” In previous works by Kirin, the words themselves (cut out, pasted, or garishly handwritten) had as much doubt about their usability and even their right to exist as a poorly maintained piano might. Kirin once again unfolds a (new) art of writing, inventing his own alphabet; an alphabet that graphically defines something missing, signs that we cannot translate into ours.

And what are our signs? These that we are seeing, those of Kirin: the ones we contemplate, do not understand, and are grateful to contemplate instead of understanding.